Low enrollment, crime on campus, a president who didn’t even last two years. The city’s only four-year public university has spent the past decade stumbling from one crisis to the next. Why getting Temple on the right path is crucial to the city’s future.

Get a compelling long read and must-have lifestyle tips in your inbox every Sunday morning — great with coffee!

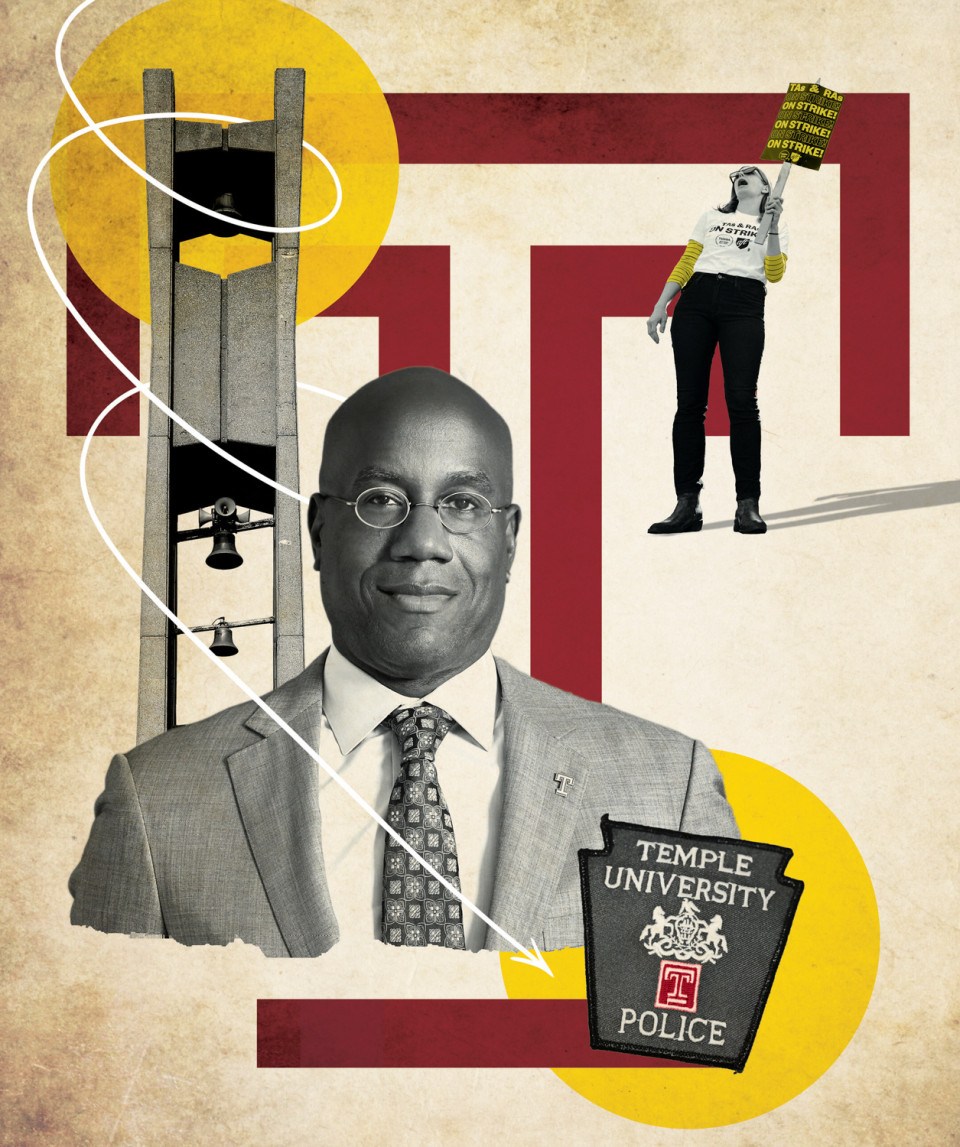

Temple University has been embroiled in a series of crises. / Photo-illustration by Leticia R. Albano (Wingard: Stuart Goldenberg; bell tower: Raymond Boyd/Getty Images; protester: Associated Press)

It was a momentous day at Temple University. Jason Wingard, the first Black president in the school’s 138-year history, was being inaugurated. Owing to the glacial time scales of the academic world, Wingard had in fact been in the job for more than a year by the time September 2022 rolled around, but the ceremony provided an opportunity to deliver a sort of keynote speech, outlining his vision for the future of the university.

Temple’s auditorium was filled with professors and administrators in their floor-length academic garb, and amid the pomp and circumstance, grandiose pronouncements flowed freely. A radio host for WURD, narrating the session, proclaimed, “It’s a true Obama moment times 10, you know what I mean? Because this one is right here in Philadelphia.” New Jersey Senator Cory Booker, a former classmate of Wingard’s at Stanford and the ceremony’s guest speaker, was no less effusive: “I don’t know if I have seen any moment in American history where you have this kind of alignment. You have the right university having the right president at the right time.”

A few minutes later, Wingard stepped to the stage. His red and blue robes were in the colors of Penn, where he received his PhD in education, culture and society, and he’d donned a tie in the cherry red of Temple. Wingard, who’d previously worked as Goldman Sachs’s chief learning officer and had been an administrator at Penn and Columbia, began by sharing a few anecdotes about teachers who had impacted his life. It was when he began talking about his philosophy of higher education that things started to get a little strange.

Wingard had recently published a book, The College Devaluation Crisis, expounding on what he saw as higher ed’s failure to churn out qualified workers. In his speech, he posed an open question: If you were Amazon and hiring a logistics worker, would you rather have someone with a college degree, or someone younger, cheaper, with no college education but who’d just “earned a digital badge in logistics management”? The answer — so obvious that it didn’t even need to be said outright — was the latter.

On the screen behind him, Wingard showed an image that had become a pet metaphor: a burning oil rig surrounded by open waters. Higher education, Wingard said, was the burning rig, and there were two options: Stay on it and burn, or jump into the icy unknown of change. “We can either continue going down and doing what we’re doing and get replaced,” he said, “or we can pivot and adapt, which is painful, to meet the market needs and survive.”

Wingard shared how he planned to accomplish that at Temple. He spoke of raising money for additional scholarships. He talked about establishing a research institute on the future of work, building a new arts and culture center in North Philly, creating a K-8 school to prepare kids in the community to one day attend Temple, and expanding Temple’s campus, which already has satellites in Rome and Tokyo, to “Los Angeles and targeted locations in South America, Europe, Asia and Africa.” It was a vision of staggering ambition, and for a moment, you could almost forget that Temple was a school facing a precipitous drop in enrollment and tens of millions of dollars in budget cuts.

In a city of universities, Temple is without question the one that best mirrors Philadelphia’s own identity — and not just because of the fiscal challenges, a declining population, and uneven leadership. It is Philadelphia’s only four-year public university. It is a school that, since founder Russell Conwell began tutoring people in a North Philly basement at night in 1884, has had a strong civic mission, an institution founded upon the ideal of access to education and the theory that you don’t need to search far and wide (or maybe have a sub-10-percent acceptance rate) to find excellence — that there are “acres of diamonds,” as Conwell once put it in a famous speech, right here in our own backyard. Maybe Temple could be doing a smidge better in that department these days — just 15 percent of the school’s 2022 freshman class was from the city — but it still educates more Philly students than any other local university. If a certain Ivy League neighbor brings students from across the country and the world into the city for four years — students who then promptly pack up for greener, more lucrative pastures — Temple represents the opposite impulse. It is the anti-brain-drain school. It doesn’t feel like a stretch to say that a strong Temple means a stronger future for Philadelphia.

Which is why it felt all the more meaningful when, just four months after Wingard gave his inauguration speech, Temple experienced a procession of crises: a punishing graduate student strike, a university police officer shot and killed in the line of duty, and the faculty union organizing a no-confidence vote against Wingard, the provost, and the chair of the board of trustees. Not even two years into his tenure, Wingard had resigned. Temple, meanwhile, found itself in a position that was starting to feel a little too familiar: lost at sea, and not entirely sure as to how it had ended up there in the first place.

•

These are tough times for higher ed. Undergraduate enrollment is down six percent nationally at public colleges since 2017. Schools are hiring fewer tenured faculty while raising tuition costs, even as good jobs for college grads are far from assured.

Temple hasn’t been immune to these rumblings. During the pandemic, violent crime rose across the country in big cities, but on Temple’s urban campus, the fear has been exacerbated by two highly publicized murders: In November 2021, undergraduate student Samuel Collington was shot just blocks off campus during a carjacking in broad daylight, and in February of this year, Temple police officer Christopher Fitzgerald was killed while on patrol. Meanwhile, almost all universities in Pennsylvania are grappling with enrollment challenges, thanks at least in part to an in-state population that’s aging and producing fewer new college-age kids. At Temple, the sense that the campus is unsafe hasn’t made navigating the enrollment headwinds any easier. Enrollment for this year is down to 31,000 students, a drop of 23 percent since 2017.

Losing roughly a quarter of your student body in six years would be a disaster for any institution; at Temple, there are structural factors making it even worse. The school is one of just four “state-related” universities in Pennsylvania, a quasi-public designation that effectively means it’s expected to charge discounted in-state tuition while not receiving as much state funding as fully public institutions. Not that fully public institutions receive much help, either. Pennsylvania ranks 49th out of 50 states when it comes to funding its higher-ed systems, and Temple receives just 13 percent of its $1.2 billion budget from the state. Fully public West Chester, by comparison, gets 30 percent. Two of Temple’s state-related peers, the University of Pittsburgh and Penn State, have endowments of $5.5 billion and $4.6 billion, respectively, helping to offset their lesser state funding. Temple’s endowment is a comparatively paltry $856 million, which means it’s especially reliant on tuition dollars to fund itself. The board of trustees voted in July to increase tuition four percent, raising the baseline cost for in-state students to roughly $19,000 a year. At the same time, Temple has cut $170 million from its budget over the past four years, and layoffs have begun: 19 non-tenured faculty recently found out their contracts weren’t being renewed, and 45 others have received one-year extensions instead of the usual multi-year agreements. Making matters worse, next year’s appropriation for state-related universities, which would have seen Temple receive a rare seven percent boost in funding, has been voted down twice in Harrisburg and is currently in limbo.

Even before Jason Wingard arrived on campus, many in the Temple faculty had been grousing that the university was stuck in a revolving door of mismanagement. After Peter Liacouras served an 18-year stint as president ending in 2000, a series of short-term unmemorable or ineffective successors ensued: David Adamany, the former president of Wayne State University, served six years. Ditto Ann Weaver Hart, who came from the University of New Hampshire. Neil Theobald, who arrived in 2013 as the chief financial officer of Indiana University with a mandate to remake Temple’s budgeting system and later to build a football stadium in North Philly, lasted just three before being forced out by the board. Temple lifer Dick Englert, who’d held 16 different positions at the university over four decades, stepped in as interim, then stuck around for five years. And then there was Wingard. In its first 120 years, Temple had seven presidents. By the time next year rolls around, it will be on its sixth in less than 25.

Then-president Jason Wingard on his bike tour of Temple’s neighborhood / Photograph courtesy of Temple University

Amid all that turnover, a good chunk of faculty has lost faith in the university leadership. “I jokingly tell people this place is run by a few old-timers, and once every few years they bring in a president, mostly for their own entertainment, and then they realize, ‘Nobody can save us from ourselves’ and they get rid of him,” says one professor. “What has gone awry in the board’s decision-making process,” wonders Steve Newman, a professor of English who’s a former head of the faculty union, “that would lead them to choose people again and again they find unsatisfactory?”

Beyond the board, professors complain there’s been a progressive erosion of faculty input into university affairs. “Layers of administrators are vested with tasks that faculty used to own,” says Tricia Jones, a longtime professor of communication. The faculty senate, the place where professors pass resolutions or complain about the way things are being run, is “now a space where administrators come in and make presentations” and little else, according to Jeff Doshna, a city planning professor who’s the current president of the faculty union. Mohammad Kiani, an engineering professor who arrived at Temple from the University of Tennessee in 2004, was amazed to see how the place operated. “There’s no faculty engagement, no faculty involvement,” he says. “Faculty have completely divorced themselves from the daily affairs of the university.” With fewer faculty receiving the protection of tenure — the number of non-tenured faculty has grown from 150 in 1999 to more than 700 in 2018, while the number of tenured positions has fallen from 870 to 750 over the same span, according to an analysis by the faculty union — there’s both more turnover and less incentive to speak up.

That can be problematic because Temple is a place where important administrators like deans can last forever. According to one high-level administrator, there was no formal system for reviewing the deans until a decade ago, and to this day, it’s not unheard-of for them to serve 20 years — an eternity in the academic world. This might simply produce problematic governance — or you could end up with a Fox School of Business situation, where Moshe Porat, one of those two-decade deans, oversaw a rankings-falsifying scheme that went on for years until he was caught in 2018, ending with Temple’s online MBA program being removed from the U.S. News & World Report rankings and Porat convicted of fraud.

Another mini dean-scandal took place in the College of Education, where Greg Anderson was accused in 2021 of screaming at faculty in meetings and punishing perceived enemies by unilaterally assigning them to other departments where they had few connections — academia’s version of banishment to Siberia. Anderson also eliminated Temple’s urban education master’s degree, a move that rankled faculty and seemed to contradict everything the university supposedly stood for. Anderson eventually stepped down as dean, but a series of high-profile professors ended up leaving Temple entirely, including Sara Goldrick-Rab, a scholar working on college affordability who had her own research center with 50 employees at the university and had brought in millions of dollars in grants over the years. Will Jordan, another defector, claims he brought complaints about Anderson to then-provost JoAnne Epps to little avail and was asked by Epps whether he could point to specific instances where Anderson had broken Temple laws or policies. “It was kind of unbelievable, like, we’re talking to you about leadership, and you’re asking us if he committed any crimes,” Jordan says. “Are you telling us at Temple you gotta commit a crime to lose your job?” (A university investigation concluded that Anderson didn’t break any laws or Temple policy, and he remained dean during Epps’s entire tenure as provost. Epps maintains that complaints never went ignored; the fact, she says, that some faculty “don’t know what response might have been taken doesn’t mean the answer was none.”)

All of this is to say that Wingard didn’t arrive at Temple at a moment when faculty were necessarily primed to trust leadership. “I’m a skeptic of any president coming in under our board of trustees, given that I don’t think our board is thinking too much in the direction of what improves education,” says Mary Stricker, a sociologist in the College of Liberal Arts. It was easy to look at Wingard’s history of working at Goldman Sachs, Wharton, and Columbia’s professional school and conclude that he was closer to Wall Street than to the academy. More than one faculty member pointed out that Wingard had never held tenure anywhere. The school where he served as dean at Columbia offered degrees in disciplines like construction administration, human capital management, narrative medicine, nonprofit management and sports management. During Wingard’s time there, some Columbia professors raised concerns in the faculty senate about the academic rigor of the degrees and speculated that they might tarnish the reputation of the university.

Whether Wingard got a fair shake from the faculty depends on whom you talk to. Doshna, the faculty union president, says he wasn’t writing off Wingard immediately and was “hopeful that Temple’s first Black president would be transformative.” But according to Jordan, Doshna’s predecessor in the union, it only took about a week for colleagues to start referring to Wingard as “President Goldman Sachs.”

•

One of the main jobs of a university president is to simply be visible. Wingard was supposed to be an external president who would excel at courting donors, but for those on campus, it was “strikingly notable how much he was not around,” says political science professor Barbara Ferman. According to Jordan and Doshna, Wingard never responded to emails asking him to meet with them in their roles as faculty union president. Nor did Wingard seem inclined to show face, even just symbolically at the beginning of his tenure, at faculty meetings like the collegial assemblies. (Wingard didn’t respond to requests that he comment for this story.)

If Wingard had merely isolated himself from rank-and-file faculty, that would have been one thing. But according to multiple administrators, he kept them at arm’s length, too. When one dean tried to send him some information on a college, word came back from Wingard’s office that any details provided to the president needed to be in the format of five bullet points — nothing more. If you wanted to have Wingard attend an event, you had to send a formal request in writing many weeks in advance, which had to be signed off on by multiple people in his cabinet. Wingard made a series of organizational changes as well, removing provost JoAnne Epps, a former law-school dean who’s been at Temple since the mid-’80s, and giving her just two hours’ notice before she had to announce the decision on a Zoom call with the deans. He tweaked the organizational chart so that the vice presidents in charge of international admissions and research no longer reported to him. Were these the necessary surgical interventions required to heal an ailing university, just as Wingard had promised? Or was this upheaval for its own sake? With Wingard keeping everything close to the vest, it could be hard to tell. “We often joked he created a firewall to protect himself,” says one high-level administrator.

If there was a firewall, it wasn’t preventing people from leaving. Temple’s director of enrollment announced he was taking a new job at the end of the 2022 academic year, creating a vacancy at a critical time as the university spent the better part of a year searching for a replacement. The head of the research office, which directs millions of dollars in grants that give Temple its coveted status as a Carnegie R-1 research institution, stepped down around the same time, leading to disarray. In one case, a representative from the National Institutes of Health sent a menacing email threatening to withhold all of Temple’s funding from the NIH’s general medical sciences department due to late paperwork, which would have jeopardized millions of dollars of annual funding. “I write a lot of grants, and that office absolutely imploded,” says Ferman. The situation did little to allay concerns about dysfunction under Wingard’s watch.

One thing Wingard did seem to have a knack for was branding. He regularly posted photos with students on Instagram. He took an extremely well-photographed and choreographed bike tour around North Philly, making stops to chat with various students and community members on their stoops. “The limited number of faculty who talked to him directly felt like it was entirely for show,” says Doshna. Even the ideas that might have been good ones, like Wingard’s announcement — made shortly after three home invasions occurred near Temple’s campus in the span of two weeks — that he and his wife would move from Chestnut Hill to an apartment in North Philly, could look from a different angle like something closer to strategically timed public relations.

One way to read Wingard’s style as a leader is that it was intentional. “These disruptor-innovators tend not to come down on the side of building relationships, because that’s just empowering the status quo,” says one professor. “They don’t come in as a partner, but to upend the tables. Except you can’t do that without relationships. Otherwise, people will do what they’ve done at Temple, which is to organize against you.”

•

None of these issues was necessarily disqualifying for Wingard. What cost him his job were twin crises, one of his own making and one that had little to do with him: the graduate student strike and the uptick in crime on campus.

The graduate student union had voted to authorize a potential strike, with 99 percent approval, in November 2022, after nearly a year of contract negotiations had gone by without resolution. The union, whose members perform a major chunk of the teaching labor at Temple University, had grown considerably in the four years since its last contract, increasing its membership from about 18 percent of its 700-person bargaining unit to more than 60 percent. A week after the union formally went on strike in late January — the first in its 25-year history — the university responded with a massive escalation, shutting off the grad students’ health care and informing them they would have to pay their own tuition, which is normally covered by the university. “I have never, ever heard of another administration trying to bill its teaching assistants for tuition,” says Newman, the former president of the faculty union. “My view is they were trying to break the union, because the one thing that will kill a union is a failed strike.”

If that was the goal, it didn’t work. Suddenly, a run-of-the-mill local labor fight became a national story. American Federation of Teachers head Randi Weingarten and Bernie Sanders sent words of support on Twitter. The Washington Post covered the strike. Meanwhile, Wingard didn’t comment publicly on what was going on. The grad students were galvanized, protesting the administration on campus and hanging a banner reading “Where’s Wingard?” on the picket line.

The picket line during the graduate student strike / Photograph by Stanley Collins

Wingard’s whereabouts eventually became known: In February, in the middle of the six-week strike, he was at the Super Bowl. It could have made sense for a university president to attend the game as a schmoozing opportunity, especially with the home team playing, but since Wingard wasn’t exactly operating with a surplus of good faith, few people were willing to give him the benefit of the doubt. Temple police officer Fitzgerald was killed that same month, and while campus safety had long been an issue, and while the university was no exception to the national trend of rising crime in cities during the pandemic, Wingard started taking flak. (According to an NBC 10 report, the number of shootings within the Temple police patrol zone increased from nine in 2018 to 26 last year.) The police union became more vocal, criticizing the administration for failing to hire more officers, though the challenge of officer recruitment, too, was part of a broader trend.

People at all levels of the Temple organization seemed to be coming around, for various reasons, to the conclusion that Wingard wasn’t the right president. “He was MIA,” says Ferman. “If things are going well, it doesn’t matter if a president is MIA, but when you have all these crises going on, you need a leader who at least is going to try to solve the problems.” Deans tried to express their concerns to the provost. A group of department heads sent a letter to Wingard condemning the decision to cut off grad students’ health care, pointing out that Temple’s actions caused “irreparable harm” not just to the students, but to the reputation of Temple itself. At the same time, the faculty union began discussing an action it had never taken before in its history: a vote of no-confidence in the president.

Those discussions weren’t without controversy. Some Black faculty members felt that the union, none of whose officers are Black, was too quick to turn on the university’s first Black president, especially one who’d come into the job during the pandemic. “Trying to single out Wingard’s administration for the problems of low enrollment and violence seemed to me as if they weren’t taking into consideration the time he came into the university and how much time he had on campus to address some of those issues,” says Kimmika Williams-Witherspoon, a professor of theater studies who’s also the head of the faculty senate. The whole ordeal left a bad taste in her mouth. “As an African American female, especially as an African American female and mother of an African American son, it felt a whole lot like a public lynching,” she says. “I was embarrassed and ashamed of some of my colleagues.” Will Jordan, the former union president, had already left Temple by the time of the no-confidence vote but says it seemed as if the union was simply trying to “embarrass the administration into improving,” a strategy he didn’t support. “Blowing up Temple is not going to make the university better for faculty, and it’s not going to make it better for the administration,” he says.

By mid-March, the grad students had agreed to a new contract with the administration that would boost their pay to $24,000 a year and eventually amount to a 30 percent raise. But the trauma from the killing of Officer Fitzgerald in late February still lingered, and by the end of March, Wingard had resigned, telling the Inquirer that a “perfect storm of societal crises” had prevented him from being successful.

A memorial to slain Temple police officer Christopher Fitzgerald / Photograph via Associated Press

With Wingard gone, the faculty union took his name off the no-confidence motion but continued with a vote against board chair Mitchell Morgan and provost Greg Mandel, in part to signal that Wingard wasn’t the root of the problem. Eighty-one percent of the membership voted in favor, though not necessarily with glee. “It was horrible that we were forced to take a vote of no-confidence in the first Black president,” Ferman says. As it currently stands, Wingard is the only person to have lost his job. “That’s a problem,” Newman admits. “I don’t think he was a good choice, and I do not lament the fact he is no longer our president, but he is only one person — while a very important person — and there needs to be a lot more soul searching.”

When it comes to that soul searching, there’s little disagreement about who should be doing it. “I lay this at the feet of the board of trustees,” Ferman says. “There’s a reason we put Mitch Morgan in that vote of no-confidence. Wingard should not have been hired.”

•

If there is a universally agreed-upon bogeyman at Temple University, a sinister yet poorly understood force, it is the board of trustees. “It’s really like a mafia,” says Jordan. “There’s no accountability; it’s a black hole.” One person who used to sit on the board describes it as a “group of older white men who make all the decisions in meetings that happen before the meeting.”

At the beginning of this story, the board was indeed seeming very black-boxy. Board chair Mitchell Morgan, a Temple grad who built a multibillion-dollar real estate empire and took over the chair position in 2019, initially declined an interview. He later agreed to answer questions in writing, though none of his legally immaculate responses was particularly illuminating as to the questions of whether he felt the board needed to change and what role, if any, it has had in the mess at Temple in the past few years.

Days later, Morgan had a change of heart. A fellow trustee, Steve Charles, a businessman and major Temple donor who’s something of a reforming force on the board, had convinced him to talk — against the recommendation of the university’s lawyers. Morgan and I spoke, with Charles on the line, on a Saturday in June, and what emerged was someone who had plenty to say about higher ed and what’s gone wrong at Temple.

For a long time, the board — which has 36 members, 12 of whom are appointed by politicians, in keeping with Temple’s semi-public character — has had a reputation as a group of micromanagers. It had that reputation because for much of recent history, it was true. Morgan’s predecessor as chair was Patrick O’Connor, half the namesake of the Cozen O’Connor law firm. Some of O’Connor’s greatest hits as board chair included talking to the press about how he wished he could fire tenured professor Marc Lamont Hill, who had made pro-Palestinian remarks at a 2018 conference that some people alleged were antisemitic. Wherever you came down on Hill’s comments, the board chair advocating that a professor be fired for public speech flew in the face of academic freedom and suggested a fundamental lack of understanding — or maybe just a lack of caring — of what a university is. O’Connor didn’t exactly help the board’s reputation, either, when it came out, in a story published in this magazine five years ago, that he spoke to president Dick Englert every single day. And then you had the Bill Cosby situation. When Cosby, a Temple trustee at the time, was being sued for sexual assault by Andrea Constand, a former Temple employee, in the mid-2000s, his lawyer was none other than fellow trustee Patrick O’Connor. (At that point, O’Connor was not yet chair.) Temple was aware of this, yet it somehow determined this didn’t represent a conflict of interest.

“I do think he was a micromanager, there’s no question about it,” Morgan says of O’Connor. As chair, Morgan describes himself as the opposite kind of leader — someone who delegates to the Temple employees who know more than he does. “I don’t think that 36 board members know how to run the university. I wouldn’t pick any of us to be president,” he says. One of his first acts as board chair was to reduce the “ridiculous” number of over-involved committees the board had. “No one’s ever accused me my entire career of being a micromanager, I can guarantee you that,” he says.

As Morgan began the search to replace Englert in 2020, almost all the prospective candidates had read about Temple’s board and had serious misgivings about the position. What kind of person would want a job where you’re going to be cut off at the knees by the trustees? Morgan says he personally spoke to more than 100 candidates to convince them “there’s a new chief in town” and that he had a “totally different philosophy than Pat O’Connor.”

According to both Charles and Morgan, Wingard separated himself from the pack as the interview process went on. “On paper, he was unbelievable,” Morgan says. The board was hunting for someone with a business background who could juice Temple’s reputation among fund-raisers and boost the school’s “pitiful” endowment. With his Stanford and Goldman Sachs and Harvard and Penn pedigree, Wingard seemed to fit the bill.

That’s not to say the search wasn’t without its bumps. When the 16-person search committee was first announced, there were no Black women included on it. Public outcry ensued, including from the faculty union, and Williams-Witherspoon and Valerie Harrison, an administrator, were both added. Some faculty still say that the presidential searches — Wingard’s being no exception — have unfolded in too much secrecy and without enough faculty input, a charge Morgan disputes. “We’ve been accused of not doing outreach with the faculty, the deans, the alumni, the community. That’s not true,” he says. “People have short memories.”

Once Wingard was hired, it didn’t take long for the board to realize things weren’t quite working out as imagined. “He is a really nice person and a big personality, but he did not engage a lot with the deans, he did not engage a lot with the trustees, and he did not engage with the public officials,” Morgan says. “That was just not his style. Quite frankly, we were all kind of shocked, because we thought of all his skill set, that would have been his best quality.” Faced with a president who wasn’t living up to expectations, Morgan felt like he had no choice but to do something that was foreign to him: He hired a leadership coach and convened a subset of the board to work with Wingard and train him. So much for a non-micromanaging board.

If you talk to enough critical Temple employees, one of the common threads that will emerge is the feeling that Wingard was exactly who the board wanted — that his philosophy is at its core incompatible with the Temple mission, and therefore his hiring can only be understood as part of a long-gestating project by the board to dismantle the current version of Temple. “They believe in this neoliberal corporatized higher-ed model,” Evan Kassof, a former president of the graduate student union, says of the board. Much of the anti-board sentiment can be traced at least as far back as the Theobald years. “There’s a misalignment of vision,” Doshna says, citing the quixotic and unrealized football stadium as an example of leadership’s misplaced priorities. To many professors, Wingard felt like an extension of the same philosophy. “What they saw was someone who represented corporate America, and that struck fear in a lot of folks,” says Jordan.

Morgan says that line of thinking is bogus. “I’ve heard rumors like we’re going to turn it into a correspondence school,” he says. “I mean, it’s the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever heard.” Morgan sees himself as emblematic of the Temple mission: someone from Philly who came from no money, who worked selling shoes full-time as he went to Temple at night. “We change lives,” he says. “We really have a much more important mission than Penn. I mean, it’s not to say Penn’s not important, but most of those kids are financially more secure. Our kids are gritty.”

When Wingard stated in his inauguration speech his view that Temple’s competition as a university was certification companies that were training future Amazon employees, Morgan claims he was as surprised as everyone else. “We do not agree with that philosophy,” he says. He believes Temple needs to modify its curriculum and tweak things “around the edges,” but nothing like the sort of perma-flux curricular changes driven by the market that Wingard discusses in his book. (Morgan says he read half of it.) The other ideas Wingard had for Temple — building a K-8 school, opening up new campuses across the world — hadn’t been discussed or vetted, either. “Almost everything he said from the stage that day was news to us,” says Charles. In this telling, the board isn’t a malevolent force seeking to deconstruct Temple that lost its mettle before it could finish the job; it’s merely inept, having hired someone whose views were incompatible with its own.

Either way, by the time of the inauguration speech, the board had already concluded that Wingard wasn’t going to work out due to his leadership defects. With Wingard facing the wave of bad press about campus safety and the grad-student strike, his position became increasingly untenable. Morgan says now that the administration’s response to the strike was “handled terribly” and that as a non-micromanager, he wasn’t very involved in the negotiations — so uninvolved that he first learned of the decision to cut off students’ health care by reading about it in the newspaper. At any rate, the implosion did offer one advantage: an opportunity to cut bait.

•

On a Friday afternoon in June, interim president JoAnne Epps sits in the president’s office in Sullivan Hall, just off Temple’s Liacouras Walk. A few framed photos have been placed across various surfaces, but the space has a kind of Airbnb anonymity to it. If Epps never fully moves in, well, it’s because she has no intention of being president beyond the next year.

Epps, who’s held positions ranging from faculty member to law-school dean to provost over her 38 years at Temple University, is unlike Wingard in many ways. She’s already attended a few collegial assembly meetings, she’s got plans to meet with the deans, and she has walked over, unprompted, to visit with faculty union president Jeff Doshna. She doesn’t believe higher ed is broken, and while she, like Morgan, thinks the curriculum can and should be fine-tuned, she doesn’t subscribe to the theory that colleges ought to be entirely responsive to the current marketplace. “I don’t even think we could do that,” she says. “It changes too quickly.” She doesn’t consider herself a disruptor, either. “There are people that love the word ‘disruption,’ as if you just break things, hope for the best, and if it doesn’t go well, you sweep that into a pile and try something else,” she says. “That is not my philosophy.”

In some corners of the faculty, there’s still a degree of unease about Epps’s appointment. The Greg Anderson dean controversy, for instance, took place during her time as provost — an occasion that might have called for a little disruption. Her selection also has a certain dissonant echo: After Theobald was ousted, Dick Englert took over as interim but eventually got the permanent gig — an era that’s most associated with stasis. The fear is that Epps is another Englert, even if she in no uncertain terms says she’s not a candidate for the full-time gig. “The last thing we need now is stability,” a professor says. “What we need now is change. Because things are not good.” Epps says she recognizes that merely holding steady isn’t really an option — the oil rig may not be on fire, but it’s at least going to require some major renovations — and that the board has explicitly told her she wasn’t selected “merely as a caretaker or a placeholder.”

What Epps believes Temple needs now is reconciliation — hence those outreach efforts to groups Wingard didn’t pay much attention to. Banking some goodwill isn’t the worst idea. This fall, the Temple faculty union’s contract will end, and you can bet it will remember how the university treated the grad students. The union has already filed grievances over the 19 professors whose contracts weren’t renewed amid budget cuts. If Epps is losing sleep over the prospect of yet another damaging labor fight, she doesn’t show it in her office. “I don’t want to overreact to the things that are ahead of us, as if the road is populated with just one monumental barrier after another,” she says.

Meanwhile, Temple’s board is gearing up for another presidential search. “I think our leadership hasn’t been great for a while,” Morgan admits, which is part of the reason why he feels the next president needs to have done the job before: “I don’t think we can afford to have on-the-job training.” He believes the next president still needs to have “some type of business background, because there’s going to be an economic side” to the job, and that with the right choice, Temple “can really change who we are and our rankings.” He intends for the search to look much like it did last time — a statement that may prompt faculty nightmares, although in Morgan’s mind, this simply means there will be outreach to Temple’s various constituencies and that, like last time, there will be representation from the faculty, the administration and the student body on the search committee. Morgan says he’s considering adding someone from the North Philly community, which happens to be one of the faculty union’s demands.

Morgan has also been thinking a bit more about the ways the board does its business. He acknowledges that from the outside, it looks as if all the board does is sit in private executive session and then show up in public to vote unanimously and without debate on resolutions. The reality, Morgan insists, is that most of the executive session consists of Temple employees making presentations to the board. In other words, not mafia behavior, although you could be forgiven for thinking the worst, which Morgan himself even seems to concede. “I think if we’re guilty of anything,” he says, “we’re guilty of terrible communication.”

That was Wingard’s problem, too. And the irony of poor communication at Temple is that almost everyone at the university — from the administrators to Morgan to the faculty who are highly critical of them both — seems to agree on the school’s mission. It is a place, everyone will tell you, with a deep-seated civic commitment. It is a place that cares about serving Philadelphia’s students. It is a place with high academic standards, and a place that (though the absurd cost of college has made this increasingly difficult) maintains accessibility is important. Morgan says he believes this. So does the faculty, and so does Epps. That ought to be an advantage for a battered university charting its path forward. The question is whether they all believe each other when they say it.

Published as “Temple on the Brink” in the September 2023 issue of Philadelphia magazine.