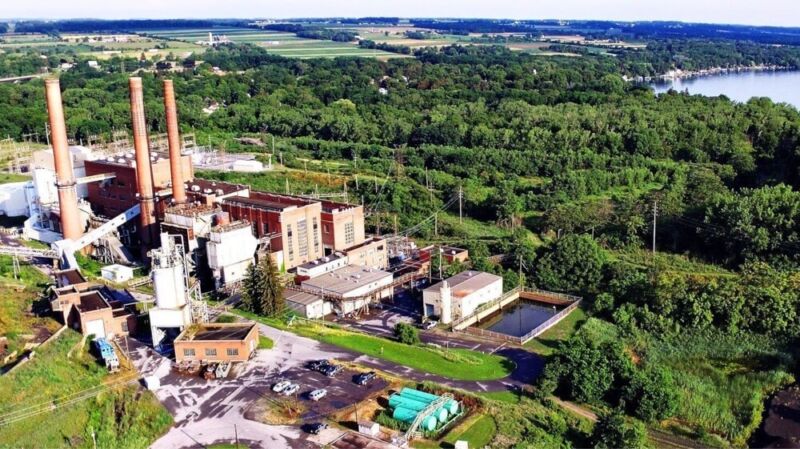

Enlarge / In this aerial photo of Greenidge Generation's power plant outside Dresden, NY, Seneca Lake is visible in the background. The lake receives warm water from Greenidge's operations.

The fossil fuel power plant that a private equity firm revived to mine bitcoin is at it again. Not content to just pollute the atmosphere in pursuit of a volatile crypto asset with little real-world utility, this experiment in free marketeering is also dumping tens of millions of gallons of hot water into glacial Seneca Lake in upstate New York.

“The lake is so warm you feel like you’re in a hot tub,” Abi Buddington, who lives near the Greenidge power plant, told NBC News.

In the past, nearby residents weren’t necessarily enamored with the idea of a pollution-spewing power plant warming their deep, cold water lake, but at least the electricity produced by the plant was powering their homes. Sixty percent still does, Greenidge said, but the rest of the time, the turbines are burning natural gas to mint profits for the private equity firm Atlas Holdings by mining bitcoin.

Atlas, the firm that bought Greenidge has been ramping up its bitcoin mining aspirations over the last year and a half, installing thousands of mining rigs that have produced over 1,100 bitcoin as of February 2021. The company has plans to install thousands more rigs, ultimately using 85 MW of the station’s total 108 MW capacity.

Seneca Lake’s water isn’t the only thing the power plant is warming. In December 2020, with the power plant running at just 13 percent of its capacity, Atlas’ bitcoin operations there produced 243,103 tons of carbon dioxide and equivalent greenhouse gases, a ten-fold increase from January 2020 when mining commenced. NOx pollution, which is responsible for everything from asthma, lung cancer, and premature death, also rose 10x.

The plant currently has a permit to emit 641,000 tons CO2e every year, though if Atlas wants to maximize its return on investment and use all 106 MW of the plant’s capacity, its carbon pollution could surge to 1.06 million tons per year, according to Earthjustice and the Sierra Club. Expect NOx emissions—and health impacts—to rise accordingly. The project’s only tangible benefit (apart from dividends appearing in investors’ pockets) are the company’s claimed 31 jobs.

Sparkling specimen

The 12,000-year-old Seneca Lake is a sparkling specimen of the Finger Lakes region. It still boasts high water quality, clean enough to drink with just limited treatment. Its waters are home to a sizable lake trout population that’s large enough to maintain the National Lake Trout Derby for 57 years running. The prized fish spawn in the rivers that feed the lake, and it’s into one of those rivers—the Keuka Lake Outlet, known to locals for its rainbow trout fishing—that Greenidge dumps its heated water.

Rainbow trout are highly sensitive to fluctuations in water temperature, with the fish happiest in the mid-50s. Because cold water holds more oxygen, as temps rise, fish become stressed. Above 70˚ F, rainbow trout stop growing and stressed individuals start dying. Experienced anglers don’t bother fishing when water temps get to that point.

Greenidge has a permit to dump 135 million gallons of water per day into the Keuka Lake Outlet as hot as 108˚ F in the summer and 86˚ F in the winter. New York’s Department of Environmental Conservation reports that over the last four years, the plant’s daily maximum discharge temperatures have averaged 98˚ in summer and 70˚ in winter. That water eventually makes its way to Seneca Lake, where it can result in tropical surface temps and harmful algal blooms. Residents say lake temperatures are already up, though a full study won't be completed until 2023.

Casting about for profits

Atlas, the private equity firm, bought the Greenidge power plant in 2014 and converted it from coal to natural gas. The firm initially intended it to be a peaker plant that would sell power to the grid when demand spiked.

But in the three years that Atlas spent renovating the plant, the world changed. Natural gas, which was once viewed as a bridge fuel, is increasingly being seen as a dead end. Renewable sources like wind and solar continue to plunge in price, so much so that by 2019, the economics of similar peaker power plants meant that 60% of them didn’t run more than six hours in a row. Today, renewable sources backed by batteries are cheaper than gas-powered peaker plants, and even batteries alone are threatening the fossil behemoths.

Though Atlas spent $60 million retrofitting the old coal plant to run on gas, it didn’t spring for the more advanced combined cycle technology, which would have helped it operate profitably if it had become a peaker plant. In the search for higher returns, the company landed on bitcoin mining, Greenidge’s CEO told NBC. After a small test suggested that mining would be profitable, the firm plowed significant sums into the project. By the end of the year, Greenidge and Atlas plan to have 18,000 rigs mining at the site with another 10,500 on the horizon. When Atlas’ plans for Greenidge are complete, mining rigs will consume 79% of the plant’s rated capacity.

Atlas won’t stop there, of course. The firm, through Greenidge Generation Holdings, will lease a building from a bankrupt book and magazine printer and convert it into a datacenter for cryptocurrency mining. Unlike the original Greenidge, this project doesn’t have onsite power, and Atlas claims it’ll use two-thirds “zero carbon” power from sources like nuclear. The rest? Fossil, most likely, and Atlas says it’ll offset emissions from both its Spartanburg and New York operations. But the company hasn’t said how, and many offset programs don’t reduce emissions as claimed.

As for the hot tub that Seneca Lake's residents say parts of it are turning into? There’s no offset for that.

Update 6/7 8:30 pm: Greenidge sent Ars details of water temperature readings taken between March 1 and April 17, stating that the water leaving the plant was 49.6˚ F, which was 6.8˚ F warmer than the temperature at the plant’s intake. Furthermore, the company points out that a water quality monitoring buoy nine miles north of the plant shows an average temperature of 67˚ F. “The Greenidge facility operates in full compliance with its air and water permits, which were issued after years of analysis and review by the State,” a spokesperson wrote to Ars. “The suggestion that Greenidge is somehow negatively impacting Seneca Lake—or is an impediment to New York’s important greenhouse gas emissions reduction goals—is just false.” We’ve also updated the headline to reflect that Abi Buddington reportedly thinks that part of the lake feels like a hot tub, not the entire lake.